Back in the days – late Seventies to late Eighties – when I was spending most of my free time in Hong Kong to learn the Hung style from master Chan Hon Chung, there was no the “lineage” thing, nor there was the rivalry that creates a climate of suspicion and a somehow wary atmosphere in today’s Hung Kuen world. Master Chan was the undisputed noble father of our style and – in many terms – of the Honk Kong Chinese martial arts world. No one questioned his role, after all he was Lam Sai Wing’s best known student and a respected bonesetter, had a four pages business card crammed with “chairman” and “president” titles, a prestigious martial curriculum. And – most of all – to no other kung fu master had been offered the honor of receiving the Medal of Glory and being introduced to Elizabeth II, queen of the British colony of Hong Kong, oddly not hated, if not respected, by the Hong Kong people.

Back in the days – late Seventies to late Eighties – when I was spending most of my free time in Hong Kong to learn the Hung style from master Chan Hon Chung, there was no the “lineage” thing, nor there was the rivalry that creates a climate of suspicion and a somehow wary atmosphere in today’s Hung Kuen world. Master Chan was the undisputed noble father of our style and – in many terms – of the Honk Kong Chinese martial arts world. No one questioned his role, after all he was Lam Sai Wing’s best known student and a respected bonesetter, had a four pages business card crammed with “chairman” and “president” titles, a prestigious martial curriculum. And – most of all – to no other kung fu master had been offered the honor of receiving the Medal of Glory and being introduced to Elizabeth II, queen of the British colony of Hong Kong, oddly not hated, if not respected, by the Hong Kong people.

Since 1938 the Hon Chung Gymnasium, at 729 of Nathan Road, was a small world where the Chinese martial culture and tradition could be met, studied and learned. No other martial places in Hong Kong were so well known, appreciated and respected: Mr. “Goodness and Kindness” was indubitably the one and only successor of the direct line that brought the pure Hung style from the ancient founder to the last Century of the second Millenium, through the legacy of the legendary masters Wong Fei Hung and Lam Sai Wing, respectively grandfather and father – from a martial point of view – of Chan Hon Chung.

Master Chan was a visionary who could combine tradition and innovation. Faithful to the original martial nature of the Chines kung fu, he also sought to highlight its natural evolution as a healthy sport, in an era in which fists and bladed weapons were no longer used to make war. This was one of the strategical points of the program that brought him to being elected president of the Hong Kong Chinese Martial Arts Association (from 2006 renamed Hong Kong Chinese Martial Arts Association Dragon And Lion Dance Association) of which he was one of the most active founders.

Unfortunately, the only goal that master Chan was not able to reach is the continuation of his school. The disease that struck him in the second half of the Eighties, the closure of the historical site of Nathan Road and eventually his death broke the “iron wire” that connected his school to the founders of the style, creating a cultural vacuum that produced adverse effects on the Hung Kuen world. None of his late best students – in spite of their outstanding martial culture and quality – picked up his leadership: the noble legacy of master Chan came to an end, giving way to people of different martial origins who had never dared to get to his level while he was active on the scene.

New Millenium, year 2016, a quarter of century jump after master Chan’s death. The diffusion of the Internet affected dramatically the Southrn Chinese martial world – and Hung Kuen is a substantial part of it – producing a generation of new masters. The good ones study, know and respect the tradition and the essential prerequisites of the martial arts. Some stick to the old methods and forms, some others are innovators and introduce new ways of training and practicing, but remaining faithful to the basic principles (side note: paradoxically the innovators are the most traditionalist: in their martial journey they follow the path of Wong Fei Hung, Lam Sai Wing and Chan Hon Chung, enlightened innovators who evolved the style, still keeping intact its essence).

On the other hand there is a generation of (self) defined “masters” whose reputation and notoriety is based on YouTube and social media promotion rather than on the quality of their kung fu, culture, human quality and teaching attitude.

Some of them put the focus on an abstract athleticism, researching the efficacy in raw power rather than quality of the gesture, teaching aggressiveness rather than inner peace and energy concentration.

Some push the limits beyond the boundaries of reasonableness, imposing harmful stances and extreme (read: wrong) positions that pollute the form and can degenerate in permanent damage to the musculoskeletal system.

Some pick up the forms from spurious sources to complete their teaching program, contaminating and distorting the style just to be able to claim and resell an alleged total knowledge of it.

Some base their teaching methods on intimidation and oppression, implementing physical and verbal menacing as primary tools to build an artificial aura of power and invincibilty.

Etcetera. I call them all the “bad masters”.

Telling the good masters from the bad ones is a decisive – yet not easy – action for any student, specially for the beginner. An effective way is starting from the roots, trying to understand how the martial arts worked in their Golden Era, what a “sifu” truly was and how he behaved. In this regard I find very useful the new e-book about master Chan Hon Chung by Pavel Macek (whom I consider one of the “virtuous” innovators among the new “good masters”): a good starting point to understand the last real Hong Kong Chinese kung fu world.

Telling the good masters from the bad ones is a decisive – yet not easy – action for any student, specially for the beginner. An effective way is starting from the roots, trying to understand how the martial arts worked in their Golden Era, what a “sifu” truly was and how he behaved. In this regard I find very useful the new e-book about master Chan Hon Chung by Pavel Macek (whom I consider one of the “virtuous” innovators among the new “good masters”): a good starting point to understand the last real Hong Kong Chinese kung fu world.

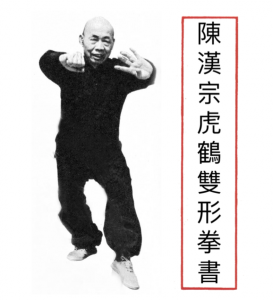

The interesting restoration and reorganization of the old shots of Chan Hon Chung showing the Fu Hok form helps to clarify the genuine stances and movements of one of the best known kung fu forms. But even more precious are the English translations of two articles from Hong Kong magazines of the Eighties that reveal the real atmosphere of the era, putting in the right places the real protagonists of the opera, the supporting cast, the extras and the spectators.

In brief: this new e-book is a precious reading that helps understanding a complicated and somehow obscure world, underlining the real values, separating the chaff from the grain, telling the real facts from the legends that were built in the following decades thanks to lack of reliable sources of information.

A document that fills a small but significant part of the gap left by the premature exit of master Chan from the Hung style world, an indispensable book in the virtual library of every martial arts student and fan.