Hung Kuen stances: a correct execution is the most important assumption for the serious student. In every martial art the forms are basically a symbolic (if not “metaphoric”) way to avoid the contaminations, aimed to keep and hand down the set as pure as possible. But every student should know that – albeit in a full respect of the tradition – a significant quantity of realism must be kept in the practice. Master Chan Hon Chung granted a great importance to this realism, that was part of his teaching starting from the stances, the actual pillars of the whole system. The old master always pushed us to keep realism in our practice of the forms, explaining that the Hung style is not about dancing or showing off, but it’s about fighting, for real.

If one thinks that the beauty of the Hung Kuen system comes from its efficacy, he should consequently acknowledge the common frills and misconceptions that pollute the pure essence of the style, rather focusing on its martial essence, avoiding the traps that can move him away from the “real thing”.

In my experience one of the main traps bringing to wrong habits originates from the standard description of Hung Kuen: “a style based on strong, low stances”. These adjectives – although technically correct – can give way to a common misinterpretation: “the lower I go, the better (or “the more hungkuenish”) I am”. This mistake produces stances that are static, inefficient, difficult to get out from, illogical and – what’s worse – potentially dangerous to the locomotor system.

Take for example the “sei ping ma” stance. Executing it with the thighs parallel to the ground – as many students proudly show on the social media – overloads muscles and tendons, creating such an unfavorable angle on the joints that the proceeding to the next position will require an unreasonable quantity of effort and time, adding a harmful load on the joints. The following picture shows a typical wrong execution of this stance:

Even the “ji ng ma” is often affected by this race to an unnatural overlowering. This mistake requires an extra rotation of the rear foot, an innatural anteversion of the pelvis producing a dangerous curve on the lumbar spine. Also, the open waist points to a side instead of pointing forward, spoiling the accumulation and explosion of energy. Last but not least, the uneven contact of the rear foot with the ground, usually on the inner edge, moves the center of balance thus making the stance unstable and unefficient. A wrong execution:

Last but not least: “diu ma”, a stance that looks so cool and “martial” that nearly every combat style has it, each one with a specific poetic name and of course its peculiar mistakes. The following video is precious, because it summarizes them all (from an Hung style point of view, but I’d dare to say from any realistic martial point of view), making any further explanations unnecessary :-)

At this point the question is: how can I defend myself and my Hung Kuen from the bad habits? In my experience I noticed that a wrong execution of the stances starts from a lack of consciousness of the waist, bringing to a wrong feet position (thus spoiling the peculiarity of Hung Kuen stances and messing up the whole body). From this consideration follows an idea for training the stances: the best and natural starting point for executing correct stances is focusing on a correct position of the feet, the foundations of the art.

Let’s go back to the three basic Hung Kuen stances: “sei ping ma”, “ji ng ma” and “diu ma” (from now I will call them stance 1, 2 and 3 for simplicity). Yes I know, there’s other stances (single legged, cross legged, etcetera, plus the “yi ji kim yeung ma used” in Tit Sin Kuen), but the stances 1, 2 and 3 are in my opinion the real pillars for the Hung Kuen student and share some extremely important common principles:

- always think in terms of “center of gravity” rather than in terms of weight

- the feet never diverge, but are parallel or slightly convergent (as physiologically and reasonably as possible)

- the heels slightly touch the ground, but the center of gravity lies mostly on the forefoot

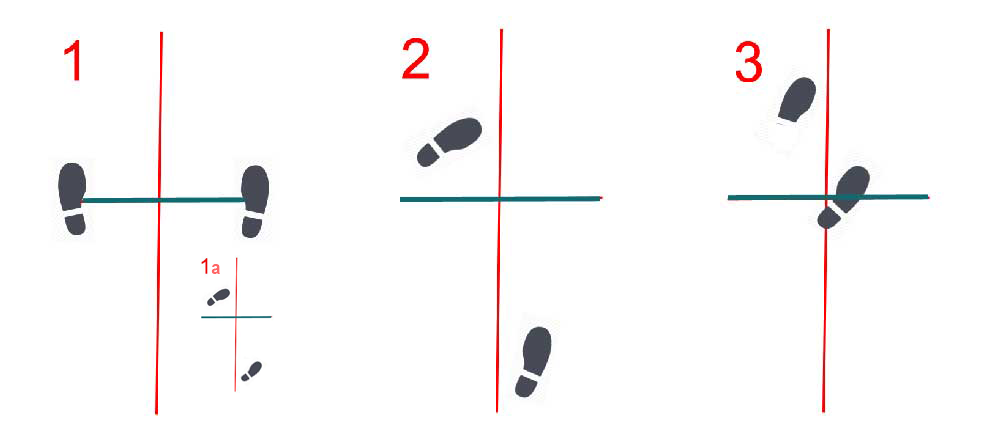

- an imaginary vertical line (the red one on the image below), the “combat line”, lies between the feet, each foot stays in its own world and (quite) never invades the other world

- there is an imaginary horizontal line (the blue one) crossing the vertical red one and indicating where the center of gravity falls (it is obviously approximate, because the center of gravity is never static and changes according to the physical structure of the practitioner)

- while executing the stances one must keep a constant attention to the core of the body: its rotations and basculations are the origin of every action

- the pelvis tends to maintain always the same distance from the ground in all the situations and stances (there are a few exceptions, but not functional to this matter)

- last but not least, the stances should never be static or frozen, rather they must be trained bearing in mind one of the most important bridges: 留 (lau4): reserving the energy in a condition of active relax.

Let’s see the stances in details, one by one.

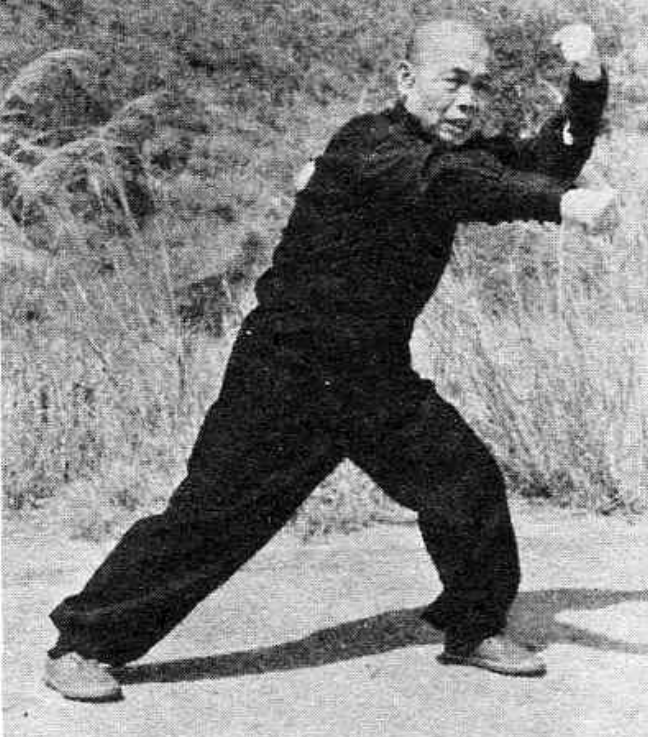

Stance 1 – the basic stance of most martial arts. The feet are parallel, approximately 1.5 – 2 times the shoulder width apart. The thighs form an angle of about 45° with the ground and the projections of the knees lie on a line that connect the big toe with the opposite shoulder. The pelvis has enough posterior tilt (a slight retroversion) to straighten the back, but not too much. The neck is straight and the head is held high. Outside the training of the basics and the intro of the forms, it is often used with some angle relative to the attack line (stance 1a), alternating it in a rhythmic sequence with the Stance 2, to create the rotating momentum of the waist that generates power. Very important: The knees do not push outwards!

Stance 1 – the basic stance of most martial arts. The feet are parallel, approximately 1.5 – 2 times the shoulder width apart. The thighs form an angle of about 45° with the ground and the projections of the knees lie on a line that connect the big toe with the opposite shoulder. The pelvis has enough posterior tilt (a slight retroversion) to straighten the back, but not too much. The neck is straight and the head is held high. Outside the training of the basics and the intro of the forms, it is often used with some angle relative to the attack line (stance 1a), alternating it in a rhythmic sequence with the Stance 2, to create the rotating momentum of the waist that generates power. Very important: The knees do not push outwards!

Stance 2 – This is a tricky stance. In theory it is as an L: bent front leg, front foot pointing inside, rear foot pointing forward, rear leg straight. In fact this is pure theory and in every picture or video the great masters of the past show less stereotyped stances. In the Hon Chung Gymnasium in Hong Kong, Nathan Road 729, the rules were: (a) front foot pointing inside 45°-60°, (b) front leg bent 45°, (c) front knee projection falling on the big toe, (d) rear leg 90% straight, (e) rear foot pointing forward as much as possible, with the whole sole touches the ground (if the rear foot touches the ground on its inside edge only, the position is wrong). Everything must be in harmony with one’s structure. Following these rules, the feet will always converge and the center of gravity drops 55-65% on the front leg. The waist is perpendicular to the striking line, with enough retroversion to straighten the back. The upper body slightly leans forward, just enough to prevent a bad curve of the lower spine. The neck is straight. This stance is frequently is achieved with from “stance 1”, which must be done correctly to allow for smooth and efficient action.

Stance 2 – This is a tricky stance. In theory it is as an L: bent front leg, front foot pointing inside, rear foot pointing forward, rear leg straight. In fact this is pure theory and in every picture or video the great masters of the past show less stereotyped stances. In the Hon Chung Gymnasium in Hong Kong, Nathan Road 729, the rules were: (a) front foot pointing inside 45°-60°, (b) front leg bent 45°, (c) front knee projection falling on the big toe, (d) rear leg 90% straight, (e) rear foot pointing forward as much as possible, with the whole sole touches the ground (if the rear foot touches the ground on its inside edge only, the position is wrong). Everything must be in harmony with one’s structure. Following these rules, the feet will always converge and the center of gravity drops 55-65% on the front leg. The waist is perpendicular to the striking line, with enough retroversion to straighten the back. The upper body slightly leans forward, just enough to prevent a bad curve of the lower spine. The neck is straight. This stance is frequently is achieved with from “stance 1”, which must be done correctly to allow for smooth and efficient action.

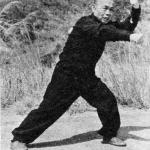

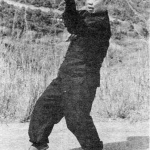

Stance 3 – The most used, showed and photographed position in the martial world, but too often poorly executed. In the Hung Kuen taught by Chan Hon Chung the feet are somehow parallel or very slightly convergent, at an angle of about 45° with the combat line. The rear leg is half bent and the tip of the front foot touches the ground with nearly no pressure, because the center of gravity is 80-90% on the forward part of the rear foot. The pelvis has enough tilt to straighten the back and is perpendicular to the striking line.

Stance 3 – The most used, showed and photographed position in the martial world, but too often poorly executed. In the Hung Kuen taught by Chan Hon Chung the feet are somehow parallel or very slightly convergent, at an angle of about 45° with the combat line. The rear leg is half bent and the tip of the front foot touches the ground with nearly no pressure, because the center of gravity is 80-90% on the forward part of the rear foot. The pelvis has enough tilt to straighten the back and is perpendicular to the striking line.

This is it: surely not a revolution, only the good old common sense, always driving the legacy of master Chan Hon Chung. Tips – rather than rules – to be executed with self-awareness, good proprioception and mental agility, always bearing in mind that the Hung boxing is never static: weather the practitioner is in active steadiness (留 – lau4), is finalising a strike (訂 – dehng6), is expanding (逼 – bik1) to occupy the opponent’s space or is translating.

Two more things: (1) every tip and rule must be followed “cum grano salis” and the awareness of the ultimate principle of kung fu: “hard work on a human scale”. (2) Every good martial art, including the widely criticized Shotokan karate, uses good stances. If you see a martialist executing a bad stance, i.e a karate guy executing a bad zenkutsu dachi (corresponding to our stance 2), maybe with the rear foot on the edge and keeping the hip open in the illusion assume a better stance, always consider that the problem is not the style, the problem is a poor execution. The good Shotokan masters (and Masao Kagawa is among them) execute stances perfectly compatible with the above mentioned principles.

On April 16, during the Covid-19 lockdown, I covered the subject in this video.