What is the Tit Sin Kuen meaning and its technical value in the martial evolution of the Hung Kuen school practitioner?

A brief historical introduction is needed, to frame the meaning of Tit Sin Kuen in the Hung Kuen school of tradition and to restore dignity to the term “sifu”. Today devalued to a mere federal degree, this appellation in the Chinese martial tradition has the first meaning of expert in a profession and broadly a master of life and a model to be imitated, consistent with its meaning of “father”.

In the martial arts schools of the last century the learning process was informal: there were no timetables, courses, exams, degrees. The program exclusively included the forms and all the rest (applications, combat, physical preparation) was entrusted exclusively to resourcefulness and creativity of the practitioners. The master (“sifu”) appeared occasionally, but in the gym there was almost always an “older brother” (“sihing”) available to teach and correct the less experienced practitioners.

The hierarchy was not tied to technical knowledge, but to the seniority in the gym, a universal parameter. Contrary to what happens today in most of the martial world, in the last Century the number of known forms had no relation with the hierarchy in the gym. For this reason the learning of the forms was not subject to limits, so that particularly enthusiastic students could complete the entire program in one or two years. This was however not considered a value, because the objective was not the quantity of known forms or the achievement of a degree, but the human and martial growth and the internalization of the basic principles of the school. These qualities were achieved with the assiduous practice and imitation of the more experienced students and – in the rare circumstances in which it was possible – of the master.

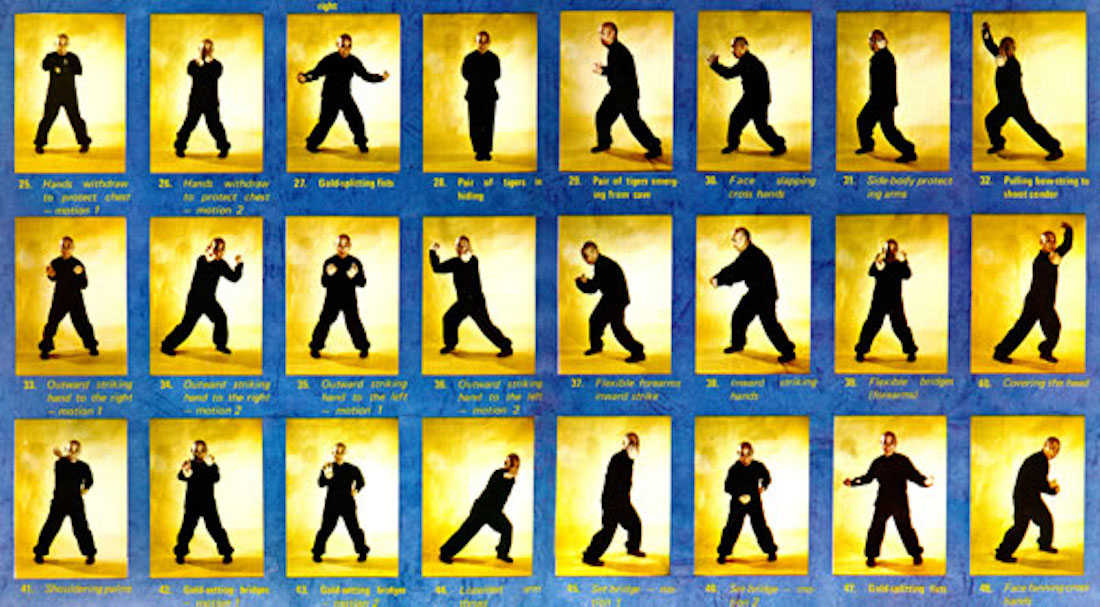

The only objective recognition of the achieved martial maturity was the access to the last two bare hands forms, which required the approval of the master: Sap Yin Kuen (“the form of the ten styles”) and Tit Sin Kuen (“the shape of the wire”).

In general it was the master who gave the first rudiments for the initial section, the “dragon”, showing the correct way to reach the position, the pelvic movements, the breath. The remaining sections (“snake”, “tiger”, “leopard”, “crane”, “gold”, “wood”, “water” and “earth”) were learned later as the other forms, according to the practice of the gym.

Sap Yin Kuen could be performed in public, while the study of Tit Sin Kuen had some limitations. The last form of the school was in fact taught privately by the teacher, who reminded the pupil of the three rules before starting, as Chan Hon Chung did when he granted me the privilege of learning it:

- you must not train and demonstrate Tit Sin Kuen in public;

- Tit Sin Kuen is not “taught” and “learned”: rather the master “hands it down” and the student “receives” it;

- those who have received Tit Sin Kuen can hand it down only with the authorization from their master, at least until he is alive.

From these three rules came the picturesque storytelling neglecting the exquisitely technical essence of Tit Sin Kuen and introducing a mystic based on esoteric concepts such as “internal martial art” and “inner energy” even “harmful to health” if performed by a beginner. In reality it is all much simpler: to be correctly executed this form requires a good internalization of the basic concepts of the Hung Kuen school, of which it is the ultimate synthesis. Particularly:

- Tit Sin Kuen explicits the transition from the stereotyped movements, aimed at athletic quality training, to the more realistic ones, aimed at combat;

- highlights the musculature of the pelvic area the engine of the continuous alternation between inhalation and exhalation, in armony with the execution of the techniques;

- underlines the importance of a dynamic interaction between stance, foot support and center of gravity;

- highlights the infinite martial sequence: perception → attention → intention → look → action → concentration → deconcentration → perception….

In the absence of understanding, internalization and application of its deep meanings, Tit Sin Kuen, this beautiful form, is reduced to a ballet seasoned with bizarre verses, which exposes the performer to the risk of falling into ridicule.

Il significato di Tit Sin Kuen e il suo valore tecnico nella scuola Hung Kuen

Qual è il vero significato di Tit Sin Kuen e quale è il suo valore tecnico nell’evoluzione marziale del praticante della scuola Hung Kuen?

È necessaria una breve premessa storica, per inquadrare il significato di Tit Sin Kuen nella scuola Hung Kuen della tradizione e restituire dignità al termine “sifu”. Oggi svalutato a mero grado federale, questo appellativo nella tradizione marziale cinese ha il significato primo di esperto in una professione e in senso lato maestro di vita e modello da imitare, coerentemente con il suo significato di “padre”.

Nelle scuole di arti marziali del secolo scorso il processo di apprendimento era informale: non esistevano orari, corsi, esami, gradi. Il programma comprendeva esclusivamente le forme e tutto il resto (applicazioni, combattimento, preparazione fisica) era affidato esclusivamente a intraprendenza e creatività dei praticanti. Il maestro (“sifu”) compariva occasionalmente, ma in palestra c’era quasi sempre un “fratello maggiore” (“sihing”) disponibile a insegnare e correggere i praticanti meno esperti.

La gerarchia non era legata al bagaglio tecnico, ma all’anzianità di palestra, un parametro universale. Contrariamente a quanto avviene oggi in gran parte del mondo marziale, nel secolo scorso il numero di forme conosciute non aveva relazione con la gerarchia nella palestra. Per questa ragione l’apprendimento delle forme non era soggetto a limiti, tanto che allievi particolarmente entusiasti potevano completare l’intero programma in uno o due anni, ma questo non era considerato un valore: l’obiettivo non era il la quantità o il conseguimento di un grado, ma la crescita marziale e l’interiorizzazione dei principi base della scuola. Queste qualità erano conseguite con la pratica assidua e l’imitazione degli allievi esperti e – nelle rare circostanze in cui era possibile – del maestro.

L’unico riconoscimento oggettivo della raggiunta maturità marziale era l’accesso alle ultime due forme a mani nude, che richiedeva il benestare del maestro: Sap Yin Kuen (“la forma dei dieci stili”) e Tit Sin Kuen (“la forma del filo di ferro”).

In genere era il maestro a dare i primi rudimenti per la sezione iniziale, il “drago”, mostrando il modo corretto per raggiungere la posizione, i movimenti pelvici, il respiro. Le restanti sezioni (“serpente”, “tigre”, “leopardo”, “gru”, “oro”, “legno”, “acqua” e “terra”) si imparavano successivamente come le altre forme, secondo la prassi di palestra.

Sap Yin Kuen poteva essere eseguita in pubblico, mentre lo studio di Tit Sin Kuen comportava alcune limitazioni. L’ultima forma della scuola veniva infatti insegnata in privato direttamente dal maestro, che prima di cominciare ricordava all’allievo le tre regole, come fece con me Chan Hon Chung quando mi concesse il privilegio di impararla:

- non si allena e non si dimostra in pubblico Tit Sin Kuen;

- Tit Sin Kuen non si “insegna” e non si “impara”: il maestro la “tramanda” e l’allievo la “riceve”;

- chi l’ha ricevuta può tramandarla solo dopo aver chiesto l’autorizzazione al proprio maestro, almeno finché questi è in vita.

Da queste tre regole è scaturita la narrazione pittoresca che dà al Tit Sin Kuen un’immagine quasi esoterica, trascurando la sua essenza squisitamente tecnica e introducendo una mistica a base di “arte marziale interna” ed “energia interiore”, addirittura di essere “nociva per la salute” se eseguita da un principiante. In realtà è tutto molto più semplice: per essere eseguita correttamente questa forma richiede una buona interiorizzazione dei concetti base della scuola Hung Kuen, di cui è la sintesi ultima. In particolare:

- Tit Sin Kuen esplicita il passaggio dai gesti stereotipati, finalizzati all’allenamento delle qualità atletiche, a gesti più realistici, finalizzati al combattimento;

- evidenzia la muscolatura della zona pelvica come come motore dell’alternanza inspirazione ed espirazione, senza soluzione di continuità, armonica con l’esecuzione delle tecniche;

- sottolinea l’importanza di una interazione dinamica tra posizione, appoggio e baricentro;

- evidenzia la sequenza marziale infinita: percezione → attenzione → intenzione → sguardo → azione → concentrazione → deconcentrazione → percezione… .

In mancanza di comprensione, interiorizzazione e applicazione del suo reale significato, Tit Sin Kuen, una magnifica forma, si riduce a un balletto condito da versi bizzarri, che espone chi lo esegue al rischio di scadere nel ridicolo.